Was Drew Smyly Trade a Salary Dump or Stroke of Genius?

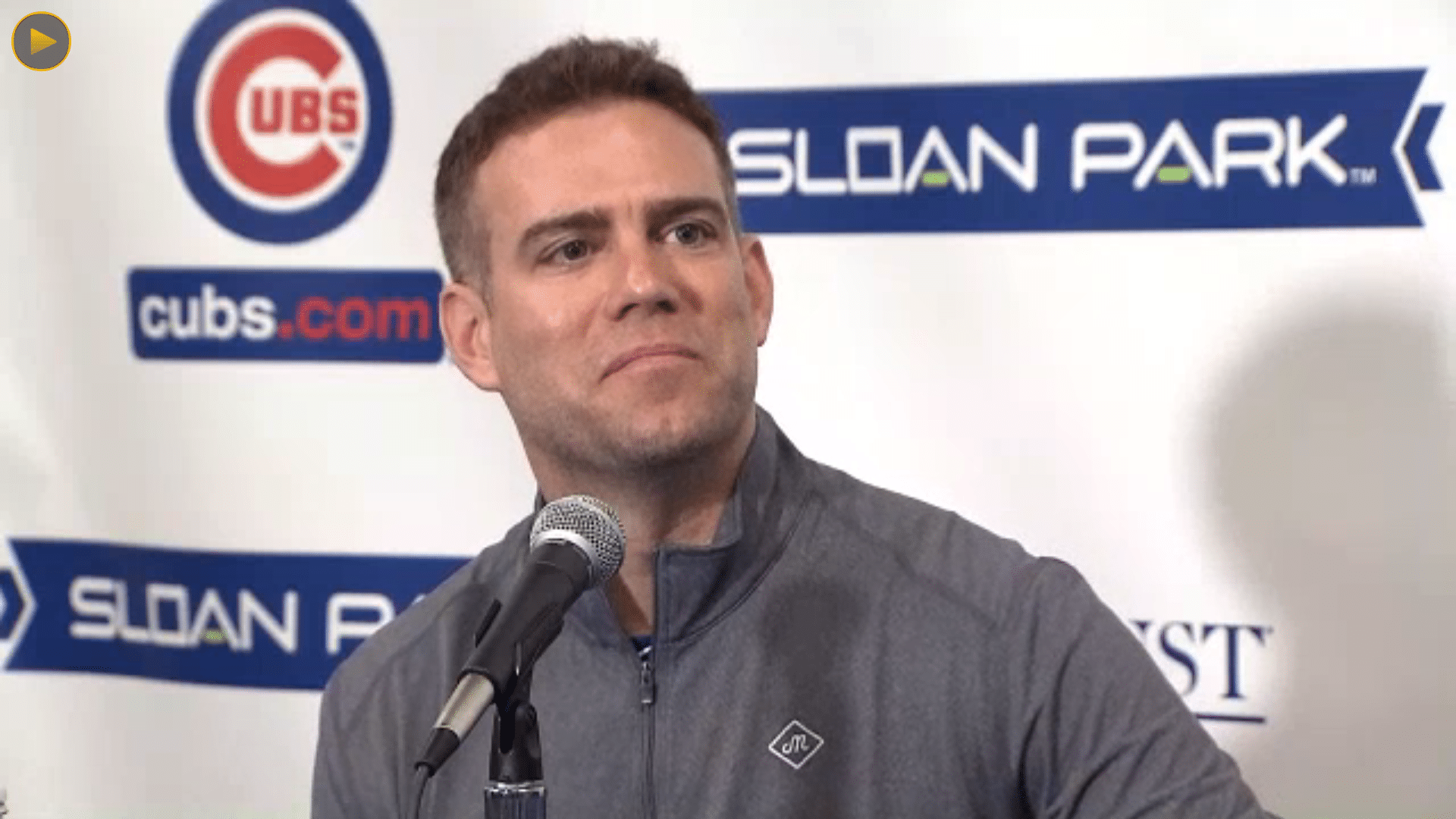

Friday’s trade of Drew Smyly set off a fun blizzard of articles and conversation among Cubs fans. On one level, it gave everyone their first fascinating puzzle piece for trying to figure out Theo Epstein’s plan for the offseason.

But largely overlooked in the Smyly trade analysis was the inclusion of those two players to be named later (PTBNL). One goes to the Cubs, the other to Texas. And I actually think those two pieces could be key to fully understanding this deal. More on that in a moment.

First, the Smyly trade reminds us how fun a Cubs offseason is to watch and analyze. Epstein has previously said no big secrets exist about the team’s strategy from year-to-year and how every move makes this abundantly clear to competitors and onlookers alike. But while what Epstein wants from each offseason may be fairly clear, how he achieves it usually involves a few inspired surprises.

Take the early part of the rebuild when Epstein’s stated goal was to “multiply our assets.” This naturally meant trading established major league players for multiple high-potential prospects and young players. It’s what every non-contender does.

What made Epstein’s approach unique was he didn’t stop at trading the likes of Matt Garza and Ryan Dempster. As with the amateur draft, he knew it takes a certain amount of luck to hit pay dirt when trading for prospects. And if each new prospect represents a bingo card, then your best chance to win is multiplying the number of bingo cards in front of you.

Epstein multiplied his bingo cards in Boston when he innovated the overslot draft approach to sign more top prospects. With overslotting banned when he came to the Cubs, he found a new way to buy more prospects. This involved signing established but rehabbing starting pitchers to over-market one-year deals. If the players returned as expected from injury in the first half, he could then trade them for multiple young players in return.

So from 2012-14, the Cubs signed Paul Maholm, Scott Feldman and Jason Hammel. While all received interest from contenders, those teams were reluctant to commit a rotation spot and too much salary hoping they’d return to form. As the leader of a bottom-dwelling team, Epstein could afford taking some calculated risk. So he overspent the market and took on uncertainty for the chance to flip at mid-season.

This is what we now call an “Epstein bank shot.” The big surprise was not that the tactic worked, but that all three pitchers named above rebounded and were flipped for significant returns. One could say it was somewhat unexpected that Feldman returned a future Cy Young winner in Jake Arrieta and that Hammel helped net a championship-quality shortstop in Addison Russell. But then again, the hope with these moves was to multiply the Cubs’ chances to hit that pay dirt.

Which returns me to Friday’s deal. In Smyly, Epstein may have just traded the 2019 version of Maholm, Feldman and Hammel. But with Cole Hamels emerging as the Cubs’ preferred pitcher to round out the starting rotation, they presently don’t have many starts available to help Smyly return to form. But the rebuilding Rangers do have that luxury, and getting Smyly gives Texas a potentially great trade-deadline commodity to flip.

So why would the Cubs give up an insurance policy like Smyly when they could later want him back if a starter falls to injury? After all, wasn’t that the exact reason they signed Smyly last year? Some wrote the Cubs just gave Smyly to the Rangers to maintain a good relationship. But no one in baseball gives other teams something for nothing, and the commissioner’s office can even block such moves. Plus, Epstein just picking up Hamels’ option and saving Texas $6 million would have bought a lot of goodwill.

No, I suspect more lies behind this trade, including some hidden Epstein sagacity.

For instance, he certainly recognized Hamels’ buyout as not just a sunk cost for the Rangers, but also as a potential asset for leveraging. By trading Smyly to Texas with the guarantee of the Cubs picking up Hamels’ option, Epstein let the Rangers turn a $6 million lost cost into a potentially flippable asset for just an extra $1 million in salary.

Surely Texas valued this, but by how much? This is where those unremarked-upon players to be named later come in.

In many PTBNL deals, a list of possible players are agreed upon at the time of the trade and the acquiring team has a set period of time to do further scouting and due diligence before selecting one. Other times, the quality of the PTBNL is based on how much value the acquired player delivers, such as when medical questions hang over that player.

What we don’t know about the Smyly deal is when the Cubs and Rangers each must select their PTBNL. Will the Cubs need to pick theirs within a couple weeks or by the end of the offseason? Or will one or both hinge on how much of a rebound Smyly makes during the first half of 2019?

My guess is 1) the Cubs get their PTBNL far sooner than the Rangers get theirs and 2) the PTBNL the Cubs get will most certainly have more value than what the Rangers receive back. This essentially makes the PTBNL for the Rangers an as-needed “value balancer.”

For the sake of discussion, let’s speculate the Rangers have agreed to give the Cubs their choice of unproven power relievers in the mold of Jose Leclerc. The Cubs choose one of them at some point before spring training. Then if Smyly has a great first half and is flipped for a prospect bonanza, the Rangers’ PTBNL could end up being a very insignificant prospect. But if Smyly fails in his return, the Cubs may need to send a higher-grade prospect back to the Rangers.

After all, getting a young power reliever would seem a better explanation for giving up starting rotation depth than merely getting a fairly paltry payroll savings of $5 million AAV.

Of course, this is all just tantalizing conjecture. But as with most Epstein bank shots, the Smyly deal will require some wait-and-see patience in order to find out everything involved. But what a fascinating opening move to what should be a highly strategic and pivotal offseason for the Cubs.