Let’s Talk About the Cubs’ Draft and Development Strategy and How It Might Be Changing

For the last few years, the Cubs’ strategy has been pretty clear: draft bats, buy arms. And while I think we can all agree that it’s not actually such a binary process, it’s not a fluke that the team’s core of young talent consists almost entirely of hitters. Consider that, while Kris Bryant, Kyle Schwarber, and Albert Almora have all made serious contributions at the MLB level, Rob Zastryzny was the first pitcher drafted by the current front office to appear for the Cubs.

And that makes all the sense in the world when you look at how the organization’s brain trust views risk. When you’re regularly picking at or near the top of the draft (6, 2, 4, and 9 from 2012-15), you can’t afford to swing and miss. Hence, the Cubs have taken hitters (Almora, Bryant, Schwarber, Ian Happ), which they believe to be less of a gamble and quicker to develop than pitchers. It’s worked, too, pretty obviously so.

But as we head into the 2017 season, after which the Cubs are facing the (probable) retirement of John Lackey and (possible) defection of Jake Arrieta, questions abound as to how the team can fill out the rotation. Whether it’s Lackey or Jon Lester, they’ve been content thus far to spend big on known commodities, even those who are past or heading in the twilight of their prime. You reach a point of diminishing returns with those investments, though, and the market for starting pitching isn’t exactly getting more reasonable.

Okay, no problem, just swing a trade for a cost-controlled starter and away you go. That sounds great on the surface and all, but it’s not quite as simple as flipping Scott Feldman and Steve Clevenger for Arrieta and Pedro Strop. That all-time fleece job was the result of a confluence of several factors, not the least of which was the Orioles’ mismanagement of Arrieta’s personality. But there’s another, perhaps just as important, reason the Cubs have heretofore been able to come out as big winners in this and other trades: they weren’t a threat.

The O’s thought a solid starter like Feldman could help them contend, while the Cubs were a doormat in the other league. Same for the A’s when they sent Addison Russell and more in exchange for Jeff Samardzija and Jason Hammel (yet another example of the Cubs’ prioritization of bats over arms). While the goal for any front office is to improve their own team, you can’t discount the fact that it’s always easier when you’re doing so with a trade partner who can’t really come back to bite you. It’s perhaps a bit much to say that pity plays a role too, but you can rest assured that the Cubs are getting sympathy from no one at this point.

We also need to look at that aforementioned free-agent pitching market and its affect on what teams are asking for those pitchers who are still under control. Knowing that even a mediocre starter can command upwards of $15 million AAV on the open market, you think a team is going to part with a young guy under team control for less than a massive return? The Rays are rumored to be asking more for Chris Archer than the White Sox received for Chris Sale. And while others surely have significantly lower price tags, you have to wonder whether the cost has risen to the point at which it outstrips the value.

Where, then, does this leave the Cubs? Phil Rogers will tell you they need to pay Arrieta, even if it means going to $200 million and as many as seven years. While I don’t disagree with the idea that bringing him back is a great idea at the right price, I’ll take a hard pass on handing Arrieta a contract anything close to the one Zack Greinke got from Arizona.

Um, Evan, what about this whole Cubs Network thing and all the various money-making ventures the Ricketts family is building around Wrigley?

Yeah, that’s cool and all, but you can’t just take all the money they print from those various revenue streams and use it to seed the clouds to make it rain cash. While the new CBA allows for an increase in the luxury tax threshold over the next five seasons, it also imposes harsher penalties for exceeding those limits. Paying Arrieta — or any top-flight pitcher — the high end of the wage scale won’t necessarily jeopardize the Cubs’ luxury tax status all on it’s own, but you have to consider the need or desire to also extend all those young hitters.

That may signal a shift toward drafting arms. Or, rather, drafting them first. The success of those aforementioned top picks tends to overshadow what the Cubs have done outside of the first round over the past several seasons. Almora holds the distinction of being the Epstein regime’s first selection, but he was followed by seven consecutive pitchers. In all, the team took 16 pitchers out of their first 25 picks in 2012 (full draft results). The Cubs took 11 pitchers in the 14 picks they made after Kris Bryant the following year.

That trend continued in 2014, when 14 of the team’s 18 picks after Kyle Schwarber were spent on pitchers. The 2015 draft stands out a bit, as the Cubs drafted only six pitchers among their first 12 picks. But the next season, missing their first two picks as a result of signing players to whom qualifying offers had been extended, the Cubs took pitchers with their first four selections. In fact, they went with arms on 13 of 14 and 17 of 20 picks.

If you’re reading all of this and wondering how the hell anything could really change for a team that has quite obviously been drafting plenty of pitchers, I can’t really blame you. After all, we’re not talking about some kind of seismic shift. Rather, it’s about how the organization prioritizes needs and tolerates risk. When they were picking early and needed to get a player who could help quickly, college bats made the most sense. Now, with pretty much every position filled for the foreseeable future, it becomes easier to draft offensive players who are a bit more raw and in need of greater instruction.

That could well mean looking to pitchers with those first round picks, loading up on those types of arms that can fill the gaps in the rotation over time. Also contributing to that possibility is the Cubs drafting later than they did in those aforementioned seasons. While history is littered with impact talent from all reaches of the draft, there’s certainly less of an expectation to find such players the further down the line you go. Again, that makes it easier to reach a little for a projectable bat or to “settle” for a safe college arm.

Now, to be clear, I’m not trying to say that the Cubs will no longer pursue veteran free agent starters or that they’ll not seek to trade for cost-controlled arms. Quite the contrary. It’s just that with their position-player depth somewhat saturated for the time being, they’ll need to develop similar strength on the mound. When it comes to negotiations, you never want to be operating from a position of need. Couple that with their position atop the competitive heap, and the Cubs find themselves without a great deal of leverage. One way to get that back, or to eliminate the need for it altogether, is to develop their own pitchers.

Again, this is all an overly simplistic look at the situation at hand. The fluid dynamics of the overall process necessitate a malleable strategy, an ability to pivot based on the opportunities and needs of both the present and future. Man, when you put it like that, it’s almost as if there really aren’t hard-and-fast guidelines dictating decisions and that any shifts are merely organic to the process and not just some forced reaction. Or perhaps I’m idealizing the machinations of Theo Epstein, Jed Hoyer, and Jason McLeod a wee bit more than is necessary.

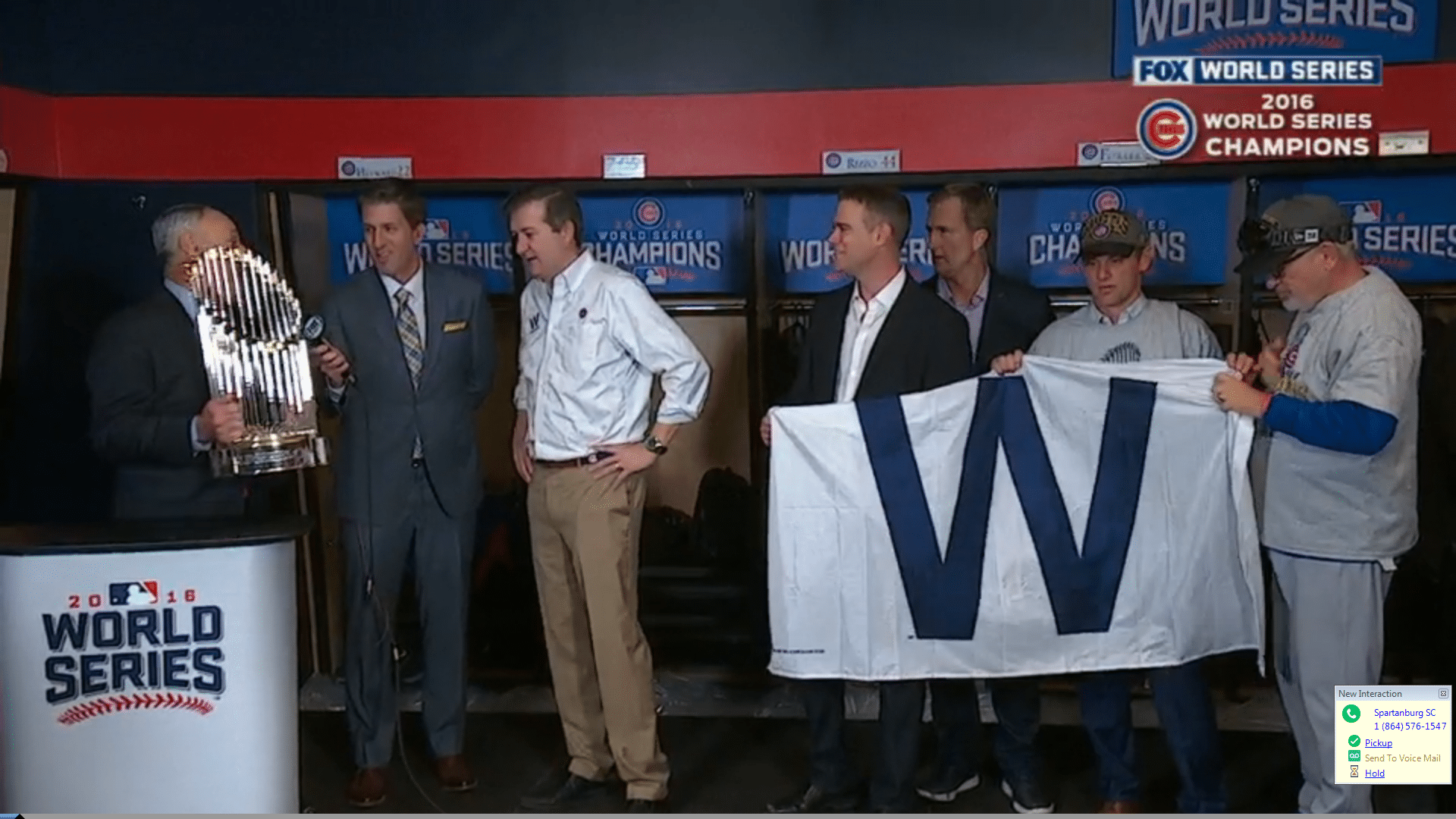

I guess what I’m trying to get at is that we can’t just look at what the Cubs have done in the past in terms of draft picks in order to know what they’ll do going forward. Of course, what they’ve done in the past is go from 100 losses to 100 wins en route to a World Series win. That’s, uh, that’s probably a decent reason to put just a little faith in the process they employ. It’s also reason to make sure you’re stepping back and viewing this whole thing as much more than some paint-by-numbers process.

That said, I do see the Cubs looking at pitchers first when the 2017 draft rolls around. I also see them kicking the tires on young, cost-controlled starters and older, post-prime stalwarts. In other words, they’re going to keep doing the same things they’ve done to get where they are. They’ll just do them a different way.