On Ken Griffey Jr, De Facto Supermen, and the Revelation of Our Own Mortality

I found a white hair the other day while readying myself for work. It was a not-all-that-unexpected sign of my waning youth, an unavoidable signpost on life’s hiking trail. Then again, calling it white isn’t really fair. It was actually more clear, the lack of pigment giving me momentary pause and forcing me to question whether I might actually have become less substantial. Then I shifted my gaze down to the over-inflated spare tire forcing the top of my boxer briefs’ waistband to submit to its expanding influence and realized that I was, in fact, becoming more substantial.

My knees creak after shooting baskets and I have to use the elliptical machine at the gym to avoid additional impact. I refer to anyone under the age of 30 as a kid. I buy pleated pants. I even had to remind myself the other day exactly what my age was. Yet none of those things actually made me feel old.

But as I watched a game at Fenway Park and saw Torii Hunter patrolling the field, my youth slipped through my fingers and circled the drain, evading my grasp all the while. Because this wasn’t former Major Leaguer Torii Hunter, but his namesake progency, a wide receiver for Notre Dame, playing at the venerable ballpark in the seventh annual Shamrock Series game. ND also boasts Corey Robinson, son of David “The Admiral” Robinson. But the Irish pass-catchers weren’t the only pedigreed players showing out that Saturday.

Ken “Trey” Griffey III, son of the ballplayer who dared to wear his hat backwards during batting practice and even (gasp!) the Home Run Derby and who hit his first home run on his own father’s birthday, caught a pass and took it 95 yards for an Arizona Wildcats score. Wait, The Kid has a kid? And he’s a junior in college?

Apparently baldness, back pain, wrinkles and other middle-age maladies don't make people feel as old as Ken Griffey Jr.'s kid playing CFB.

— Jeff Passan (@JeffPassan) November 22, 2015

I understand the hyperbolic brush with which Passan is painting here, as embellishment is sort of my milieu as well, but he’s kidding himself if he can’t see why many of us would feel this way. Athletes were — and, to an extent, still are — superheroes come to life. They were demigods who could leap over or run through walls, but who never tossed up bricks. The immortality we perceived in them provided a wellspring from which we could draw the sustenance Ponce de Leon so longed for.

Our own outward signs of age matter little because we know we can always return to that fountain of youth. It’s guardians are, after all, supermen. Those heroes and heroines provide an opiate to the people who have intrinsically tied their vigor to those athletic exploits. But there inevitably comes a time when the morphine wears off, when we awake confused and in paid, soaked in a frightened sweat. When did our idols grow old? Who allowed this?

This confusion is ratcheted up by the fact that the aging athlete in question — at least in the tweet — is one who was perhaps as closely associated with the bloom of nonage as any before or since. This isn’t the first time we’ve been reminded of Junior’s middle-agedness either. His name was trending recently in the wake of his 46th (forty-sixth!) birthday and his upcoming candidacy for the Hall of Fame.

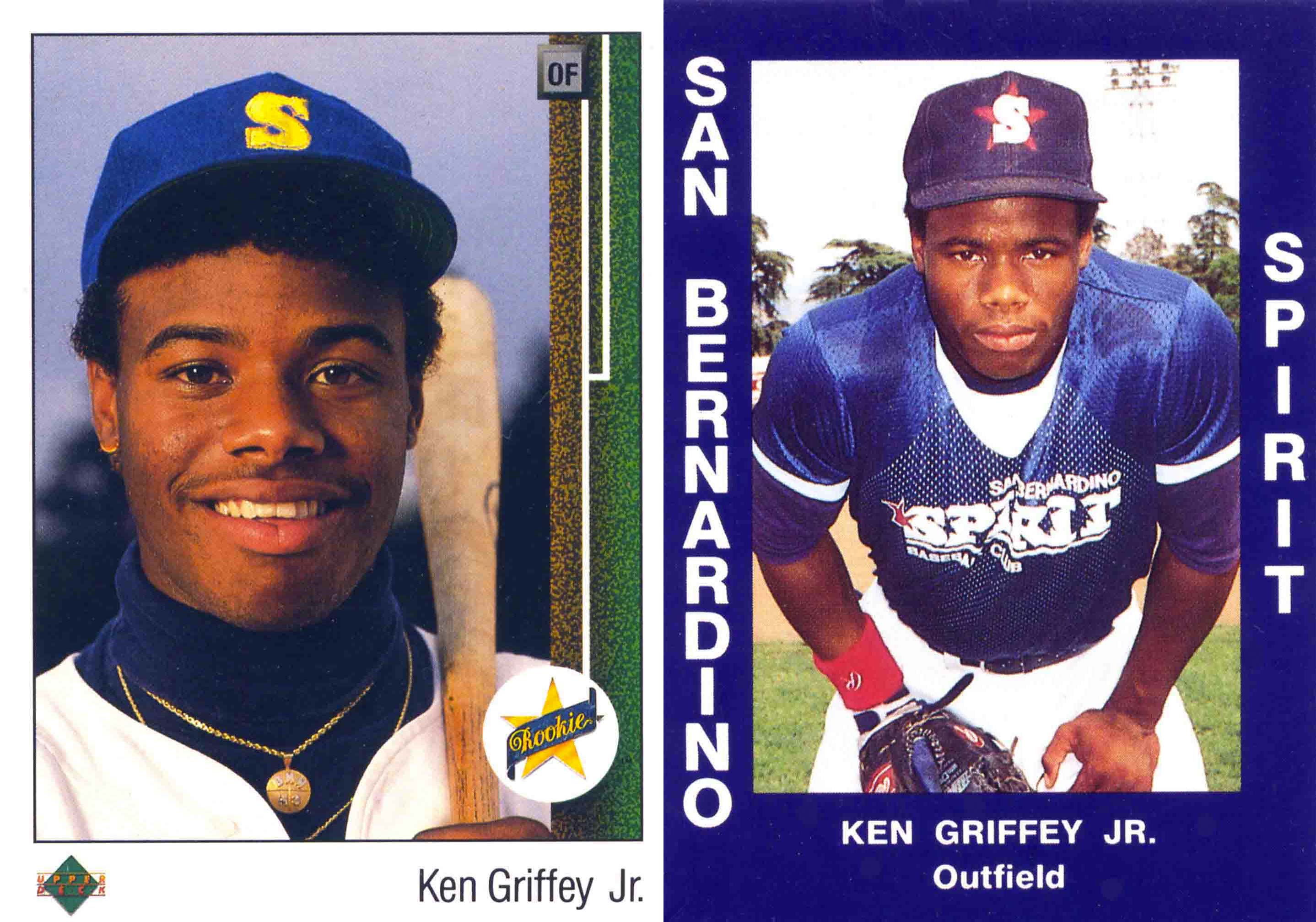

Therein lies another source of our incredulity at Griffey’s mortality. He debuted just over four months after he turned 19…almost 27 years ago. He played in parts of 22 seasons in Major League Baseball, through lingering injuries that stole his transcendent greatness from us almost as much as they did from him. But despite the changing jerseys — does anyone really remember that abbreviated campaign with the White Sox as anything other than a bad trip? — the enduring image of Ken Griffey Jr remains that of the smiling youngster, hat to the back as he practiced that picture-perfect swing.

And then there was that grin, a million watts of metal halide that shone so bright as to mask from us the shadows that had grown as long as Griffey was in the tooth. No man can outrun the inexorable march of time, and so even The Kid was finally drawn into the parade ranks and made to proceed in lockstep as those of us in the crowd watched on. But this isn’t really a loss, far from it.

Those athletes we once looked up to eventually become a looking glass through which we see ourselves. Seeing them aging ages us, but it also forces us to sever those ties that had bound us to the identity of another. That’s not always fun though, is it? We want to keep going back to that well and drinking deeply, postponing the admission of reality even if we’re simply hitting the snooze button once more. But hey, if you promise not to tell anyone else, I’ll let you in on a little secret.

There will always be new players coming up, new smiles to light the way. One need look no further than Bryce Harper or Kris Bryant, Carlos Correa or the Mets entire rotation, to find new fonts (I’m partial to Calibri) of life-giving water. The nature of sports is such that they constantly renew themselves, and us by extension. Knowing this won’t Just-For-Men my hair and it won’t shave those extra inches from my waistline, but it may recalibrate my thinking.

Let’s see if I’m feeling the same after my pickup basketball game Monday night.